Thomas Procter

Thomas Procter

(1753-1794)

Died aged c. 41

Thomas Procter was born on 22 April 1753 to Robert and Ellen Procter, who also produced three girls. Robert was the owner and landlord of the Spread Eagle Inn. His father, also named Thomas, had established the inn as a licensed premises in 1734, when the existing seventeenth-century building was re-fronted in a more modern vernacular Georgian style. One can imagine the early years of Thomas' childhood spent in the bustling environment of the inn, which must have seen a marked increase in trade after the opening of Settle's turnpike road in 1753.Thomas' artistic ability was in evidence from an early age. Whellan's directory of 1838 describes Procter's connection with the Spread Eagle and notes that "on the walls the dairy are still presented some of the efforts of his juvenile years". Sadly, no sign of these sketches remains today. As an intelligent child, Thomas did well at Giggleswick School, attending from about 1765 until 1771. On completion of his studies, his father apprenticed him to a tobacconist in Manchester, which at that time was developing into a thriving industrial centre. However Thomas' stay there was a short one and he soon travelled to London, finding work as a clerk in a city merchant's counting-house. It is likely that during his time employed in this trade, Thomas continued sketching and painting, perhaps more as a hobby than with any intention of pursuing art as a career. However, we may wonder whether his move to London was intended to take him nearer to the institutions of artistic excellence which were well established in the capital by this time.Around 1775, two separate occurrences changed the course of Thomas' life. As a resident of London and an artist, he must have frequented the numerous galleries and art-houses in the city. It was during one of these visits that, as Brayshaw notes, "he accidentally caught site of Mr (James) Barry's picture of 'Venus Rising from the Sea'." This greatly inspired him in his own work, which began to include more historical and allegorical subjects. Then, in September 1775, he was provided with the means to make a serious career from his art. His father had died in Settle and left him an inheritance of £100. Quitting his job at the mercantile house, Thomas spent the next two years painting and sketching, gradually building up a portfolio of work which, by 1777, had secured him a place as a student at the Royal Academy.During the three years he spent in classical training at the RA, Thomas' art work was revolutionised and he was greatly encouraged on receiving a premium from the Society of Arts for the continuance of his studies. According to J.T. Smith "he lost a great deal of time trying to be a painter, but when at length he began to model, he astonished the studios". Indeed, it is for his sculpture that Procter is best remembered, although his efforts on canvas were not quite as bad as Smith would have us believe. In fact, shortly after completing his training, the RA awarded him two medals. The first was for a sketch "Portrait of a Lady" (silver, 1783), the second for an historical scene from Shakespeare's "The Tempest" (gold, 1784). It was on receiving the latter that Thomas was carried aloft by his fellow students around the quadrangle of Somerset House, chanting "Procter, Procter! Hurrah, hurrah!".But Thomas knew that his real talents lay with clay modelling and sculpture. Working from his lodgings in the Strand, he produced a less than life-sized terra cotta model depicting "Ixion on the Wheel". Displayed at the Royal Academy exhibition of 1785, this model received great critical acclaim as an outstanding piece of sculpture. Horace Walpole described "Ixion" as "a prodigy of anatomy, with all the freedom of nature", and the model was so highly recommended by Sir Benjamin West, that Lord Hume was persuaded to purchase it for his own collection.Procter's star was now well and truly in the ascendancy. With the patronage of great men such as Hume and West, he would no doubt have felt that a prosperous career lay ahead of him. Convinced that sculpture was the most natural and successful medium in which to continue. Thomas spent twelve months producing his greatest work yet, an enormous model entitled "Diomedes Devoured by his Horses". The piece was exhibited in 1786 and Gunnis observed that its great size and dramatic subject matter "attracted a great deal of attention at the Royal Academy, but failed to find a purchaser, though the sculptor asked only fifty guineas for it". With a jolt, Thomas had discovered the fickle nature of the art world.Disappointed and dejected, he was forced to take the sculpture back to his lodgings. Unfortunately, it would not go through the door of his room, and in a fit of utter despondency he smashed the model to pieces. Thomas' confidence in his own abilities must have suffered a severe blow on that day. He had spent most of his inheritance on furthering his art, only to find himself without a patron and with his greatest work in pieces on the lodging house stairs. His misery was compounded when he learned of his mother's death in Settle shortly afterwards.Despite inheriting the various properties that constituted the Spread Eagle, which by this time was a successful coaching inn, Thomas had no intention of becoming a landlord. Although he now had fairly extensive assets, most of them were tied up in land or buildings. What he really needed was ready cash to revive his career. Returning to new lodgings in London in about 1789, Thomas began to produce an increasing number of paintings, many of which were portraits. These probably represent his greatest source of income during this period, small commissions with a guaranteed sale. He also continued painting historical and Biblical subjects—the accompanying sketch depicting "The Destruction of Daniel's Enemies" dates from about 1791 and is typical of his work from this period. The finished painting was purchased by Hume, proving that the artist enjoyed a measure of success in his later years.Between 1786 and 1791 there is no evidence that Thomas produced any more sculpture, at least not for exhibition. His earlier disappointments, combined with the cost of materials and the amount of time needed, probably discouraged him. When he did produce one final sculpture for the Royal Academy exhibition of 1792, a group in plaster entitled "Pirithous, Son of Ixion, Destroyed by Cerberus", it received the usual "paean of praise and no sale" (Brayshaw).The final years of Thomas Procter's life have been documented by several authors, although the different versions have become confused and are often tainted by romantic reflection. We know that the Royal Academy, at Sir Benjamin West's behest, chose Procter to embark on a three-year study tour of Italy, to start in the summer of 1794. This was an excellent opportunity for Thomas, as well as being a deserved recognition of his talents. For the last couple of years he had exhibited without providing an address, so there was some difficulty in tracking him down to pass on the good news. Smith takes up the tale: "West.. .found him at length, dying of starvation and disappointment, in an attic in Clare Market... and a few days later the artist died". This dramatic account tends to obscure the facts behind Procter's death.West did find Thomas and told him of the forthcoming trip to Italy, but it is doubtful that the artist was in such a poor state as Smith and others claim. From Brayshaw's research we know that Procter was living in Maiden Lane, not the Clare Market slums. Also, it is unlikely that he would allow himself to starve when we know that he owned a good deal of saleable property in Settle. The real cause of Thomas' demise lies with his trip back to Craven to prepare for his study tour. He had obviously decided to release some money for his trip because, in April 1794, he conveyed his property to the trust of his uncles, instructing them to sell some of it and clear any debts in his absence. Journeying back to London on the outside of a stagecoach, it appears he caught a severe chill which, according to Brayshaw "developed into a violent cough, causing a blood vessel to burst".Thomas Procter died in London on 13 July 1794, virtually on the eve of his departure for Italy. The tour would surely have encouraged him to resume sculpture, perhaps to achieve even higher standards of excellence. His death was lamented by his peers at the Royal Academy, who paid his work the high praise to which he had become accustomed during his life, but which had counted for little in the absence of commercial success. Perhaps the last word on this interesting painter and sculptor should go to Professor Richard Westmacott who, lecturing at the RA years later, described Procter's "Ixion" and "Pirithous" as "the work of a true genius".

OpenPlaques

Commemorated on 1 plaque

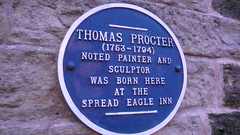

Thomas Procter (1753-1794) noted painter and sculptor was born here at the Spread Eagle Inn

18 Kirkgate, Settle, United Kingdom where they was born (1753)